13

Easter Break

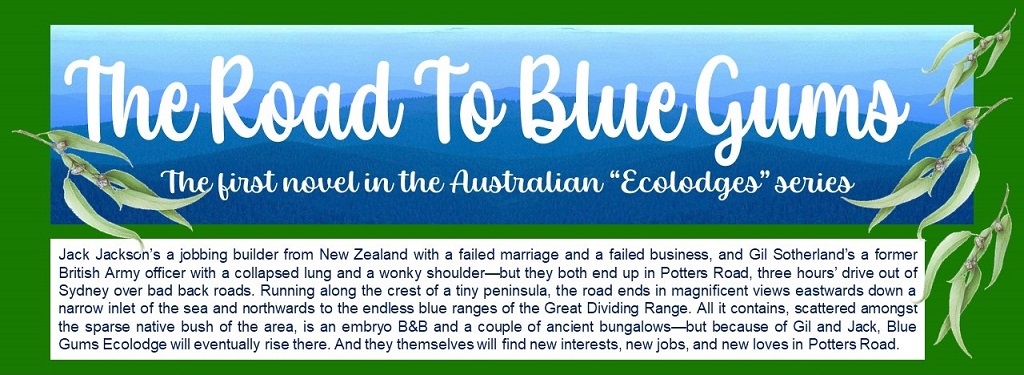

The workers had put in some really hard yacker on Blue Gums Ecolodge since the beginning of the new year—hardly any weekends off, either, at least not for the project manager and the site foreman—so by the time Easter rolled round George and Jack were more than ready for a break.

“It’s not a surf beach, of course,” said Jen apologetically. “But you do get quite good surfing there round this time of year.”

“Quite near Byron Bay,” put in Phil.

“Y—Shut up, Sotherland, you’ve been up there once!” retorted George. He peered at the map. “Aw, yeah.”

“The weather should still be good,” said Jen on a hopeful note.

“Yeah. Um, where’s the state border?”

Looking mildly surprised, Jen pointed.

George sagged. “Aw, yeah, so it is. Well, yeah, sounds all right. Um—nothing wrong with Queensland, only me ex is up there,” he explained.

“I see. Um, well, I don't want to pressurize you, George,” she said nicely, “but, um, Aunty Heather and Uncle Ken can’t keep the room if they get another booking.”

“No, ’course not,” agreed George kindly. Sweet little kid, wasn’t she? That young tit of a Phil didn’t deserve her, really. “Well, whaddaya reckon, Jack? Long weekend out of ruddy Susan’s reach?”

Jack had merely looked silently over their shoulders while the pointing and considering was going on. “Go on, ya talked me into it,” he drawled.

“Good-oh. Done any surfing?”

“Only up Piha,” he replied temperately.

“Well, that’s the Kiwis’ main surfing beach, isn’t it?” George encouraged him.

“Yeah.” Jack scratched his silvered curls. “Um, well, didn’t do much after Keith left. It’d be a good three years since I was last up Piha, George.”

“Three years? That’s nothing!”

“See, he hasn’t been on a surfboard since he was nineteen!” explained Phil with a laugh.

“You can talk, you fell off your ruddy boogie board,” returned Jen on a note of tolerant scorn.

“Uh—aren’t those the things you only lie on, Jen?” groped Jack.

Jen’s clear grey eyes twinkled. “Yeah, that’s right.”

“Yeah, go on laugh,” said Phil resignedly over the older gentlemen’s splutters. “I tell you what, Jen! We could go with them! Pitch a tent in your aunty’s back yard, why not?”

“There isn’t a back yard, they put a pool in for the motel guests,” replied Jen literally.

His face fell. “Oh.”

“Look, you kids take the room, if you want to!” said George hurriedly.

“No, he has to stay and help Gil and Ted,” replied Jen firmly.

“I only said I might and anyway, they’re doing costings and stuff, I can’t—“

“You said you would, so you’re gunnoo. And anyway, who’s gonna groom your Palomino if you’re not here?”

“It hasn’t come yet!” he cried indignantly.

“No, but it’s on its way. Or are you gonna leave all that to Gil?” she asked in steely tones.

“Um, no. –But it won’t come!” he burst out.

“It’ll come,” said Jen calmly. “We better suss out horse boxes for hire, eh? Might be a bit of a demand over Easter, so if it does arrive that week we better book one.”

“Yes, um, why would there be a demand? Oh—races?”

“That, too. No, long weekend, all the people that do dressage and show jumping’ll be out in force, practising.”

“Mm, you’re right. Pony-clubbers, too. Well, okay, we’d better book one—but it won't come,” he predicted glumly

“It’ll come!” replied Jen with a laugh. “Don’t be so pessimistic!”

With that she gave George and Jack the contact details of her aunt and uncle’s motel and removed herself and him.

“We’ll have to go, now,” noted Jack.

George cleared his throat. “Yeah. Oh, well, it’ll be a decent break, and we don’t have to surf. Could just spend all our time knocking back the frosties.”

“That’d be a hardship! Actually I quite like the beach, wouldn't mind getting in a bit of surfing. Only drawback about living up here, really.”

George groaned. “You coulda gone down to the beaches any time!”

“No transport.”

“You can use Dad’s heap any time, ya tit!” he shouted.

“Not for stuff like that,” replied Jack on a note of finality.

“Look, the Blue Gums job is paying you a decent whack, bite on the bullet and get yourself a car, Jack!”

“I’m gonna, only I gotta save up a bit more, first.”

George sighed but didn’t offer to make him a loan, he’d tried that once before and it had gone over like a bucket of lead. “Yeah. Well roll on, Ginger Bay.”

“Why Ginger?”

“Don’t ask me. Not after Ginger Rogers, I’m almost sure. Maybe they grow ginger in them parts?”

“Is it warm enough?”

“Near Byron? Bound to be, mate!”

Okay, right, he was the Aussie, he oughta know. Though come to think of it he hadn’t known how close Byron Bay was to the state border.

“Um, how close to the Queensland border is your ex?” he ventured.

George shuddered. “Far, far too close.”

“On the coast?”

George shuddered. “Yeah.”

“Right. Goddit.”

“See, what we won’t do, we won’t go near anything that looks arty-tarty or holistic or related in any way, however remote, with anything connected with spas, aerobics, vegetarianism, health food, Hindu whatsits, yoga or Bali anything,” decided George.

Jack eyed him drily. “Were we gonna, anyway?”

Shaking slightly, George conceded: “You got a point! No, well, thing is, lot of it up that way.”

“Um, yeah, isn’t Byron Bay the place where Honey’s mum lives? She’s into the weirdo shit, too.”

“That’s the word,” said George with satisfaction. “Weirdo. We’ll stick to the pubs and the good old Aussie meat pies, agreed?”

“Too right,” he said, very, very mildly.

George looked at him with immense liking. “Yeah. Come on, since we’ve knocked off we might as well nip down the pub.”

“What about Andy?”

“He’ll’ve gone down hours since,” said Andy’s son simply.

Jack didn’t ask where Ted was, he already knew he and Gil were in the sitting-room of the Jardine place surrounded by miles of computer print-outs and calculators and computers and had been since ten minutes after the blokes on the Blue Gums site knocked off at four-thirty.

“Righto, let’s go,” he agreed.

The motel wasn’t bad. Called itself Marine Breezes, though it was a block back from the beach, but that was par for the course. Not too fancy, probably dated back to the Seventies but someone had given it a lick of paint quite recently over the concrete, and the sign, which featured a sort of wave top with a sort of seagull above it, was freshly painted in white, navy and turquoise behind the flashing green neon, um, wiggle. Heather and Ken Barrett, Jen’s aunty and uncle, were okay, made them very welcome, said just to let them know if there was anything they wanted, wised them up about the best fish and chips shop, and warned them off the Ginger Thai, not that either of them needed warning, really, it was too bloody close to Hindu whatsits and Bali crap. True, they did then reveal that Heather had fixed them up for dinner on the Friday with her best friend’s cousin Junie and her friend Joanne who’d come up from Melbourne for the Easter break and were staying in unit 6, next to theirs, but it could’ve been worse: they might’ve fixed them up with them for the whole weekend.

“Technically they’ll be dogs,” warned George, sitting down heavily on one of the twin beds and removing his sneakers by the simple expedient of pushing hard with the toes of one foot against the heel of the opposite sneaker.

“Yeah.”

“Ever been out with a physiotherapist?” he added moodily. –Junie was a physiotherapist.

“Yeah, once. Not long after the divorce. Marriage in ’er eye. Very hygienic.”

George blinked. “Uh—I suppose it is a kind of medical profession, after all.”

“Yeah.” Jack unlaced his boots slowly. “When I say hygienic, no beer in bed and ya not only have a nice wash beforehand, ya have a nice wash straight after and never mind the party of the second part’s using a condom, ya gotta have a towel on the bed.”

George was seen to gulp. “Oh. One of them,” he said lamely.

“Yeah.”

“Um, these washes: was that her or you? Or both of you?”

“Before was both of us, straight after was her.”

“Right, goddit. Okay, what about a dame that works in a lawyer’s office?”

“Bit out of my socio-economic bracket, George,” replied Jack snidely.

“Come off it!”

Jack got up in his socks and investigated the little fridge. “Gee, well stocked up. Want a beer?”

“They’ll charge like a wounded bull for it—oh, go on, we are on holiday. What they got?”

“Um... Toohey’s, Foster’s, um, something German.”

“Well, not the German one, thanks very much, what sorta nongs do they think we are?”

“It’s there for when ya’ve drunk the others and finished off the vodka and the Jack Daniels and the Bundy and you’re desperate, not to say too drunk to—”

“Yeah, yeah. Chuck us over a Toohey’s, for Pete’s sake!”

Jack chucked him a can of Toohey’s and took one for himself.

“Aah!” reported George. “That’s better! –Wish we hadn’t stopped for pizza so early.”

“Could order something in?”

“Yeah, Ken reckons that restaurant up the road’ll send something in up until ten-thirty: whaddis the time?”

“Ten forty-nine,” replied Jack drily.

“Bugger. Okay, there’s gotta be a pizza place, chuck us those brochures on the lowboy, wouldja?”

Obligingly Jack gave him the brochures, though warning: “It’s a really small place, there won’t be much choice, I shouldn’t think.”

“There’ll be more choice than there is at Potters Inlet, mate!” he retorted with feeling.

“That’s true.”

“Go on, have ya done a lady from a lawyer’s office?”

“Nope. Done a lady lawyer once, though,” said Jack reminiscently.

“Really?” said George weakly.

“Yeah. Built on an extension for her. One of them condo blocks, I did the plans for her and then she hadda get the agreement of all the owners and then get planning permission: took ages, thought the job had fallen through. But she came good in the end.”

George was just about to order pizza: he choked and dropped the receiver. “You bugger!” he gasped, scrabbling for it whilst still endeavouring to remain supine on his bed. “You said that on purpose!”

“Not really, it just come to me and then I thought it was too good to pass up.”

“Yeah, like the lady lawyer, presumably!”

“Mm.”

“Hang on, I’ll just order. Want your usual?”

“If they’ve got it—yeah, ta.”

George shuddered but conceded: “They got something like it, yeah. Calls itself Neapolitan but it is like that bloody La Scala one you like. Black olives and anchovies, before you ask.” He ordered a Neapolitan for Jack and a Hawaiian for himself, remarking sadly as he hung up: “They haven't got that four cheeses one, or the meaty one, either.”

“Just as well for your cholesterol count,” replied Jack drily, drinking beer.

“Yeah.” George drank beer. “Any packets of nuts in the fridge?”

“Yeah, if you want to pay five dollars per macadamia, George!”

“Not really. Well, go on, tell us about it!”

“Eh? Oh, the lady lawyer? Nothing much to tell, really. She’d of been pushing forty, divorced, really smart sort of dame, nice city suits, kind of thing—well, tightish, but respectable. Very generous with the tea and coffee, always put out a nice packet of biscuits for me when I was working on the flat and she hadda be at work. She wanted me to double the size of the living-room—push the wall out, ya see—and put in a carport for ’er. No, well, she never come on to me. Only then there was a big do coming up—not at work, but the lawyers were all going, and the bloke she was supposed to go with stood ’er up.”

“Don’t tell me she asked you to go with ’er, Cinderella!” he gulped.

“Eh? No, are you mad? No, it was on a Friday night and I turned up at work like usual on the Saturday, and come in for me smoko, and she was bawling all over the kitchen.”

“So you consoled her.”

“I made her a cuppa and got her a fresh box of tissues, you nit.”

“Supportive,” approved George.

“Shut up!” he choked. “We had the tea and a few biscuits and she burst out with the lot. This type had had her dangling on a string for years—not one of the Auckland lot, he was from Wellington and apparently been telling the poor moo he was gonna ditch the wife. Anyway, I told her he wasn’t worth bothering about and she’d be better off dumping him and she seemed a lot better so I went back to it, and round about lunchtime she come out and asked me if I’d like some lunch ’cos she’d bought in a lot of stuff, expecting him to spend the weekend. It was a real nice lunch, bit fancy, I suppose, only tasty, ya know? Talking of olives, she’d done a chicken thing cooked up with olives and lemons—it was sour, but good.”

“Jack, wouldn’t she of had to make it that morning?” said George dazedly.

“Eh? Yeah, she had, but she said cooking took her mind off things and relaxed her. She always used to do a lot of cooking in the weekends: I think it was true.”

“Right,” he said dubiously. “Cooking always seemed to make bloody Gwyneth even more up-tight than what she was most of the time.”

“Yeah, Rosalie was like that, too. But Diane, that was her name, Diane, she wasn’t. So we had the chicken and drank this really expensive dry white she’d got in for the bugger—German, it was, talking of unaffordable. Real hock. Never had anything like it, before or since. Unbelievable. Then she had a separate salad course. Bit odd, but nice. Diced beetroot with those little pointed white things, think they’re Dutch or something.”

“Those things that look like uncircumcised pricks? Susan sometimes has those, in her most up-market fits. Aren’t they bitter as buggery?”

“Yea-ah... No, but them and the beetroot, they sort of, um, balanced each other.”

“They’d need to. So what’d you have for dessert?” he asked sardonically. “Lady lawyer?”

“Nope, just coffee and a brandy—hadda go through to her bedroom—you needn’t smirk, she’d moved her sofa in there ’cos I’d ripped the wall out of the sitting-room and it was waterproof but not nearly finished, I was getting the carport up before the weather broke. Anyway, sat on the sofa and after we’d sunk a fair bit of the brandy she put her hand on me leg—well, she could see I was up for it, she was quite a luscious type when she wasn’t in them suits, and she was just wearing old tracksuit pants and a fuzzy old jumper over a tee-shirt and the tits.”

George had a coughing fit.

“So we just took it from there. That shit from Wellington didn’t know what ’e was missing.”

“Another Desirée Garven, was she?” said George heavily. Why didn’t he ever meet luscious dames that had the hots for him and didn’t mind showing it?

“I wouldn’t say that. But keen. Come like the clappers two minutes after—well, you know.”

“I can’t say I do, but I get your drift, yeah.”

“There musta been some lady lecturers at that bloody place you used to work at, George!”

“Not in our department, though. No, well, I did use to go over to the Senior Common Room every so often. Usually ended up drinking beer with me old mate, Pete Outhwaite. Most of those females were married: all they ever seemed to talk about was the latest problems with their kids.” He shrugged. “Sitting on the sofas and chairs while us blokes propped up the bar.”

“Cripes, didn’t know that still went on amongst the professional classes.”

“Look, drop it! It’s our colonial past, or something! Or possibly it’s just that all Aussie blokes are shit-scared of women.”

“You get that one off Susan?” returned Jack drily, getting up to get them refills.

“Uh—no. Shit, did she say that to you?”

“Yeah.”

“Wonder who the poor sap was?” said George in a hollow voice.

“Don’t think it was anyone in particular; she was pissed off with the lot of ’em.” He handed him a can. “Have another. Anyway, that was my sole experience of anything what come out of a lawyer’s office. She came home early on the Monday especially to catch me before I knocked off and said it had been very nice but it was a mistake.” He shrugged. “She made a lot of noise for a mistake, but there you are.”

“Her loss, mate,” said George firmly, drinking. “Well, you want the lady from the lawyer’s office, then?”

Weakly Jack replied: “Um, well, no, but I dunno that I fancy another hygienic physio, neither.”

“Understandable. I’ll take her: hygienic or not, they’re guaranteed not to fall for yours truly.”

“Um, might be really keen, George,” he offered weakly. “Well, they are on holiday, eh?”

“Two unattached dames on the prowl? We should be so lucky! They’ll let us buy the drinks and the meal, and it’ll be thanks very much and ta-ta! –Either that or they will be dogs.” He waited but funnily enough Jack didn’t contradict him. “Dogs,” concluded George. “You want the Jack Daniels?”

“Nope.”

“Good, I’ll have it.”

“It’s your stomach.” Amiably Jack fetched it for him, into the bargain finding a glass—it was probably a tooth-glass but it looked clean—and putting ice in it.

“To oblivion!” said George, drinking deeply. “Aah! –Ooh, good, that’ll be the pizza!” He bounced up. “I’ll get it, you see what’s on the idiot box!”

“It’ll be the same as back home.”

“No, sometimes these places have”—George opened the door—“porn channels!” he said eagerly to the startled little Chinese face. “Um, sorry, mate; that for MacMurray?”

“Unit 5, one large Hawaiian, one large Neapolitan,” the boy confirmed in an Aussie drawl.

“Good-oh,” said George weakly. “Paid over the phone, okey-doke?”

It was okey-doke, but he gave the kid five dollars anyway, and was bidden “Thanks, mate. Have a good evening!” on the strength of it.

“I can’t see any porn,” reported Jack.

“Blast. Oh well, put the footy on.”

Jack didn’t say maybe there wouldn’t be any, he knew bloody well there would. On at least two channels, most probably. ...Yeah, it was a choice between Rugby League on one of the commercial channels or soccer on SBS.

They had settled back resignedly to watch League, when there was a knock at the door.

“That had better not be those dames,” warned George, getting up. “Oh, gidday, Ken. –Eh? Yeah, we sure would! Thanks, mate!”

He came back sniggering. “Fancy Emmanuelle?”

“Shit, is it?”

“Yep.”

“Well, shove it in the player, what ya waiting for?”

George shoved it in the player, providently grabbed some more beer from the fridge to save getting up again, and they settled back with slabs of pizza in their hands...

There were a couple of hysterical yelps during it, and some muffled sniggering, but on the whole Jack wasn’t wrong in concluding: “I’d probably have found that real hot when I was nineteen.”

“Yeah, me, too. Oh, well, naked dames can’t be bad. –Nightcap?”

“Haven’t you drunk enough?”

“Not booze, Heather said she’d popped some Milo in the cupboard for us.”

Milo on top of Emmanuelle. Oh, well. Amiably Jack agreed to a nice warm mug of Milo.

Funnily enough one of the consequences of eating a huge meal of pizza and beer late at night and watching feebleized dirty movies—well, apart from rising very late, very thirsty, and having to gulp down some Panadol for the head—one of the consequences was that you discovered you wouldn’t half mind a bit. George didn’t remark on this phenomenon: he was bloody sure Jack was experiencing it, too.

“That was Ginger Bay,” he noted, as, having bought ice creams, neither of them being up for anything solider, they walked through it and out the other side.

“Yeah,” admitted Jack feebly, looking about him at nothing. “Not ginger in that field, is it?”

“Nope. Broccoli.”

Jack peered. All right, if he said so.

“Well, it’s a nice day,” said George feebly. “Try the beach?”

“Ken said surf wasn’t up,” Jack reminded him

“No, but we could go for a swim.”

They did that. Then they just lay on their towels for some time. Prudently with their shirts on.

“Could suss out that pool at the motel?” ventured George.

Jack made a face. “I hate swimming in chlorine.”

“Yeah. It’ll be full of kids, too, heard ’em shrieking in it earlier. Oh, well. ’Nother swim here?”

They did that.

The little town seemed to be full of tourists, all more or less in their swimmers, but George and Jack went back to the motel and changed out of theirs, which made it about time to go to the pub, so they did that.

By that time they were quite hungry, but gee, they couldn’t grab a bite, could they? It being Friday, they were slated for Junie and Joanne. Oh, cripes.

“If we chicken out our names’ll be Mud, and what’s more it’ll get reported to Jen, ’cos families are like that, and she’ll tell Phil, because they always do, and then it’ll be all round that mob up Potters Road and personally I’m not up for never hearing the last of it from ruddy Walsingham,” noted George sourly.

“He’s all right. Bit sarky,” replied Jack tolerantly.

“Yeah, the type that never lets ya hear the last of it! Bob Springer’ll pounce on it, too.”

“All right, we better not chicken out, then.”

Glumly they returned to the motel, showered and changed...

Oh, God, there they were in the lobby, as arranged. “Yoo-hoo! You must be George and Jack!”

Oh, God. Junie, the physiotherapist, was a brightly made-up woman of, at a conservative estimate, forty-nine. Very curvaceous figure, tight flowery frock, very bright, matched the lipstick, with, talking of ginger, flaming ginger curls. Flashing earrings. Joanne, the lawyer’s clerk, was a brightly made-up woman of, at a conservative estimate, forty-nine. Plumpish figure, tight, bright pink shiny frock, with a mop of yellow curls. Flashing earrings.

They would love a drink! Fancy that.

Junie had a margarita and Joanne had a fallen angel, after which it become rather clear rather fast that Junie fancied Jack dead rotten. Okay, no skin off George’s nose, there was nothing to choose between ’em and if a plump bottle blonde was his fate, so be it. Joanne was, actually, quite a nice woman, if obviously out for a good time this Easter. Divorced, two kids, the girl was doing her nursing training and the boy was in the Navy—his choice, but at least it wasn’t the Army, he wouldn’t be sent to horrible Iraq! True, Iraq had very little coastline but there had been an Australian naval presence out in the Persian Gulf for some time, hadn’t there? George kindly didn’t say so. He just got in another round and tried not to calculate how long it’d be before the giggling Junie’s hand got onto Jack’s leg...

They fancied the Ginger Thai but George would have bet his last cent on that one. He’d of just given in but good old Jack came out with: “Nah, sorry, but I’m allergic to Thai food. Dunno whether it’s the chilli or what.”

Junie thought it might be the prawns and they then had a discussion about allergies, it was very interesting to learn that Joanne’s cousin Bill was allergic to beestings, if not entirely relevant, and yes, it was odd how the kids these days all seemed to have allergies to peanuts, it had never been heard of when Junie was a kid!

There was a nice Fasta Pasta but it’d be full of families on a holiday weekend. It was an awful pity about Jack’s allergy because the Ginger Thai was the best place, really... Junie and Joanne exchanged glances and then Junie said on a breathless note: “Look, if we go up the coast a bit there’s a really lovely Spanish-style restaurant, really unusual!”

“Up the coast?” said George in a hollow voice.

“Towards Queensland?” asked Jack, poker face.

Junie gave a squeal of laugher. “Silly! It only takes about twenty minutes.”

“Where is it?” asked George firmly.

“Um, like I say, just up the coast, George,” said Junie feebly.

“What settlement is it in, he means,” explained Jack stolidly.

Actually it was just out of Byron, on the outskirts, not in it, so although it was quite popular— George didn’t even think “Byron Bay prices?” he just got up and said: “Right, sounds good, let’s go.”

“Thought Bryon Bay was south of us?” muttered Jack as the dames pushed off to the Ladies’. “Down the coast.”

“Yeah, it is,” replied George drily.

Jack choked.

“She get her hand on yer leg, yet?” he asked drily.

“Nope. Bit of knees-y, that’s all.”

Oh, God. George sighed. “Look, they’re sharing a room and we’re sharing a room, so how do you imagine anything’s gonna come of it?”

“We can take their room and you can have ours. Unless Junie passes out before it gets to that stage.”

“She strikes me like a dame that’s used to holding her margaritas, Jack. You wanna drive?”

“Look, George, if you drive and don’t drink you might be in there with more than a chance with Joanne! What’s wrong with her? Seems like a nice woman, and she’s obviously up for it!”

“Yeah. Well, all right, I’ll drive.”

They did that.

The Spanish place called itself Andaluz, which might’ve been Spanish, who knew? It was fairly full of Byron Bay trendies, probably not a good sign, on the whole. George had once been dragged to a tapas bar by his mate Pete Outhwaite, who was interested in food, but although this place did have tapas on the menu, it also had several hefty mains, each one odder than the last. Junie and Joanne knew a lovely tapas in bar in Melbourne but this place was lovely, too! Um, yeah. Choice between the “Cordero Asada à la Andaluza”, boned roast lamb rolled up round a mixture of chestnuts and orange peel, he’d been served even weirder perversions of roast lamb at Susan’s dinner table, or a pork thing that called itself “St Jacob”, which George was pretty sure wasn’t a Spanish name, fried and crumbed with ham and cheese, in other words a schnitzel. Cheese with pork? Ugh! Well, either of them, if he wanted meat, or the ruddy duck thing that Jack was having, kind of stewed in a Madeira sauce with green olives, ugh! Junie urged the “Tortilla de Patatas” on him but in the first place George had thought tortillas were those flat Mexican breads, and in the second place, if she said it was a Spanish omelette, okay, but he wasn’t at a flaming fancy restaurant in order to have a ruddy omelette! Joanne thought he’d like the “Habas à la Asturiana” but George didn’t even listen: dried broad beans, never mind if they had a bit of chorizo sausage in them, were vegetarian muck, and he’d had enough of that during the two years before bloody Gwyneth pushed off to Queensland with the Lezzies. And they could draw a veil completely over the other mains, thanks, because kidneys and sweetbreads were both disgusting.

The discussion over the firsts went on for ages, of course, but they finally decided to have the mixed tapas platter, if they had it between them it wouldn’t be too much and they’d have plenty of room for— Yeah, yeah. When it came it included dainty helpings of guess what? Kidneys in a sherry sauce and sweetbreads in a revolting white sauce. George just ate the garlic prawns—they were okay, garlic prawns were garlic prawns, whether they called themselves Spanish or not—and a couple of little slices of spiced sausage—not bad. No, ta, Jack, them vegetarian chickpea fritters were all yours. Lovely, were they, Joanne? Yeah.

Actually the roast lamb was delicious. The Spanish-style red that came with it was only so-so, however, so George wasn’t too sorry he was driving.

Funnily enough on the drive back Junie was practically down Jack’s throat, so they went off to the dames’ unit.

Which left George and Joanne, didn’t it?

“Ooh, it’s not quite the same as ours!” she discovered, getting onto one of the beds, kicking off her shoes and popping the pillows behind her back. “I like the turquoise better, ours is in shades of yellow. The same carpet, though.”

“Yeah, they’d’ve got it wholesale. Um, well, fancy a drink, Joanne?” said George weakly.

Joanne beamed at him. “I shouldn’t, but actually I’d love one!”

No kidding? He tried the fridge. No beer left except the German stuff. Uh—was that a weekend’s supply they’d started off with, then? Um, well, the Jack Daniels had gone and at some stage last night he sort of thought Jack had drunk the Scotch, so, um... “Well, there’s vodka, Bundy or tequila,” he said feebly.

“A vodka and lime’d be lovely, thanks, George!”

“Um, no lime.”

“We had a bottle,” she said in surprise. “You know, Schweppes. It’s fizzy but it goes good with vodka.”

“Um, think someone might of drunk it this morning, um, well, I do remember I drank the Schweppes lemonade, I was quite thirsty.”

“Ya don’t say!” replied Joanne with a loud giggle. “I wonder why! Well, rum and Coke?”

“Yeah, okay, there is some Coke,” he discovered with relief. He took a German beer, he didn’t like vodka and tequila tasted like varnish.

“Come and sit down, George,” she said, patting the bed beside her,

Feebly George came and sat beside her.

“Cheers!” she beamed.

“Cheers, Joanne.” Well, yeah, it was good beer but on top of what the bloody restaurant had set them back?

Since it was Friday there was nothing much on TV except football and that pop muck the ABC always broadcast on Friday nights. God knew who watched it, it was miles behind the times, so the kids wouldn’t—he knew his own kids never had—and too flaming puerile for anyone over the age of thirty to bother with. Left the performers’ mates, didn’t it? Hopefully Joanne asked if they had any videos or DVDs.

George winced. “No. Well, um, try the radio, if ya like.”

She tried the radio. Some local commercial station, who cared? Middle of the road stuff, not the tuneless, rhythmless but very loud pop the kids went for these days, so George didn’t raise any objections. There was always the hope that it might help to drown out any noises from the next unit, too.

Then she had to see if the dimmer switch on their main light worked—handily placed between the beds, it was. Ooh, yes, it did! That was better! Cosier!

George drank beer desperately. “Yeah. Hey, ever had this German stuff? Not a bad drop.”

Very pleased to hear it, Joanne told him all about the European tour her and Andrea (possibly) and Chris (sex undetermined) had been on. –Uh, yeah, if you ended up in Bavaria around October you would come in for the Oktoberfest: right. Cheeky Germans, eh? Right. Oh: drank far too much beer and it had all been a flop? Well, that was the usual result of drinking far too much beer, yeah!

“Um, yeah, that was bad luck,” he managed.

It wasn’t clear why this led on to the topic of Rome and bottom-pinching Italians, but it did.

“Um, yeah, they’re known for it. Um, well, one of me cousins was there about five years back—well-endowed girl, bit like you, actually—and she said she was black and blue after one bus ride.”

“Exactly!” said Joanne with a loud giggle. “It helps to be a blonde, they say!”

“Right.” Desperately George topped up her drink with the rest of the Bundy and a bit more Coke. He was searching desperately for another topic of conversation but didn’t need it, because Joanne very kindly gave him a lot more details about her trip, and then launched into how they’d been on this cruise the next year, you know what those cruise boats can be like, but this one was very nice, a lot of people of their own age, no awful yobs at all.—Well, no, if it had gone all the way to Fiji it woulda been a bit out of the yobs’ price range.—Chris, it appeared, had got off with a very nice man, Ian Something, he was a New Zealander, divorced, they kept in touch and were planning to go to Rarotonga this Christmas, actually, and Andrea had had a fling with a nice American—well, older, but it hadn’t really mattered. Though he had had a pacemaker and in her shoes Joanne would have been really nervous, y’know? But Andrea had taken it in her stride, she was that sort of person.

‘So did that leave you out in the cold, Joanne?” said George kindly. “Not much fun.”

“Oh, well!” said Joanne bravely. “You get used to it. I was never one of those popular girls, at school. Funny how things turn out, isn’t it? When me and Roy got married I thought that this was it: you know, for life.”

“Yeah; ya do. It was the same with me and Gwyneth...” Somehow George found he was telling her all about it, while he finished the German beer, and she finished the Coke and the vodka. There was some gin at the back of the fridge so it seemed silly not to share that, with the remaining bottle of Schweppes—uh, ginger ale? Okay, gin and ginger, why not? They were in Ginger Bay, after all! Gales of giggles from Joanne and with the aid of the very last of the gin and ginger in his glass and a belt of tequila and ginger in hers, and that lonely-looking packet of macadamias, George told her a lot about the Blue Gums Ecolodge project.

“Isn’t this fun?” said Joanne with a laugh, leaning back against the pillows and wiggling her toes happily.

“Yeah, ’tis, actually!” admitted George.

“Is there any Coke left? Those macadamias were salty.”

“No, afraid not. Um, well, there’s a machine just up by the office, I’ll grab some, shall I?”

“That’d be lovely! What about a kiss first, though?” she said with a loud giggle.

Okay, George was up for that, so he bent over her and— Let Joanne plaster herself to him and practically choke the life out of him, cripes, it was like being kissed by one of those sucker-fish things!

“Whew!” he gasped, coming up for air.

“That wasn’t bad at all!” said Joanne with a giggle. “I am thirsty, though, George.”

“Sure! I’ll grab you that Coke!”

He dashed out, had the usual fight with the bloody vending machine but won it, rushed back in with the Coke, and gee, there she was, completely passed out, snoring.

George looked limply at the heap of bright pink shiny stuff and rather a lot of pale, plump Joanne in the dimmed light. Oh, bugger! Just his luck! He waited a bit but she showed no signs of coming to, so he covered her feet and shins with the duna—it didn’t get that cold at night up this way but he’d woken up with cold feet this morning—uh, yesterday morning, whatever—and, hesitating over it but finally getting undressed, got into the other bed.

He woke up around sixish and she was still snoring. He went to the bog and took a couple of Panadol for the head—musta been the gin, there was sure as Hell nothing wrong with that German beer, best drop he’d ever tasted—but funnily enough the sight of pale bits of Joanne bulging out of that pink thing wasn't all that discouraging when he came back, so he got into his swimmers—they were cotton shorts, what used to be called baggies way back when—put his tracksuit on over them and, letting himself out very quietly, pushed off to the beach.

“You all right, mate?” said a cautious voice.

George woke with start. “Uh—shit, did I drop off?”

It was a tall, slim, well-muscled, very tanned woman of around his own age, in a bikini top and black wetsuit pants. “Yeah,” she confirmed unemotionally. “Lucky the cops didn’t grab you, you’re not allowed to sleep on the beach round these parts.”

“Uh—no, I only came down around six.”

“Oh—right. Only been here half an hour myself, came round the point.”

She was, he now registered, carrying a surfboard under one arm. “Uh—on that?”

“Yeah, paddled round. Why?”

“Um, well, it’s quite a way,” said George feebly.

“I wouldn’t say that. You okay?”

“Yes, I said, only came down around six, I haven’t been passed out all night.”

“No, I got that, mate, I’m asking you if you’re all right.”

“Oh! Well, who’s all right, over forty-five, these days? Though I s’pose up in these parts you get some that’ve managed it, eh? Yeah—no, I’m fine, thanks; the little woman hasn’t chucked me out or anything like that, and I’m not about to do a Harold Holt.”

“Think that was probably vanity on top of drinking all night, not that we’ll ever know, in a country that locks its elected representatives’ papers away for thirty years.”

George blinked and took another look at her. “You said it! –I’d say you’re right about the vanity,” he added thoughtfully. “I’ve always kind of thought that, too. Thought he was King Canute, eh?”

“Too right!” she said with a laugh, sitting down beside him and gazing at the sea.

George couldn’t think of anything to say, so he just looked at the sea, too, and from time to time glanced at her chiselled profile. Well, not his type, really—or put it like this, lean, sporty girls had never looked twice at stodgy George MacMurray in his youth, so he’d never tried one—but she was very good-looking in her way. Not pretty, but a pleasure to look at. Well, if you could say a person was like an artefact, that was what she was like. You occasionally saw it in athletes—of either sex, gender didn’t come into it.

“Beautiful day, eh?” she said with sigh.

“Mm, wonderful.”

“Yeah. Unfortunately it’ll be filling up with tourists soon,” she added glumly. “Dunno why they come, if all they wanna do is rush round shrieking or lie under their bloody sun umbrellas listening to their bloody ghetto-blasters.”

“No. Well, I suppose a few come for the surf.”

“Mm. Metre and a half, if you’re lucky. It’s often not bad about this time of day, then you don’t get anything much until the evening.”

“Right, be when the surf patrols go in, would it?”

“Yeah!” she agreed with a choke of laughter. “If you can call them that. Tim Flanegan’s twins, they’re about eighteen and as thick as he is, and their mate, Kyle Goldsmith, he’s older but he’s solid concrete between the ears to make up for it. They are capable of staring at the beach for hours on end, I’ll grant ya that.”

George laughed. “Right! Not Bondi Rescue, then?”

“Eh?”

“Um, you know, that mad TV programme,” he said feebly.

“Haven’t got a TV. –They’ve made a TV programme about surf-lifesavers at Bondi?” she croaked.

“Yeah.”

“Okay, I can die happy,” she concluded drily.

“Yeah. It’s not the world I grew up in, that’s for sure.”

“Mm. So why are you kipping down here, if you don’t mind me asking?’

George made a face. “It’s stupid.”

“Human behaviour usually is.”

“Uh—true. Well, um, me and a mate came up from Potters Inlet—you won’t know it, about three hours out of Sydney, it’s practically landlocked, the inlets wind inland for miles. Get to it from Barrabarra if you’re going by road. Anyway, we just fancied a weekend away with a bit of sun and sand. He used to surf quite a bit in his younger days. Um, well, the neighbour’s boy’s girlfriend, stop me if this is getting too involved, jacked us up at a motel run by her aunty and uncle—they’d had a cancellation, you see. When we got here we found the aunty had jacked us up for tonight with a couple of dames, um, friends of a friend or something, that are up here on their own. Um, we are all divorced, it was pretty harmless. Jack, my mate, he got off with the ginger-haired one—well, she got off with him, took one look at him and went for it—he’s a good-looking bloke, they usually go for him. Left me with the other one. She was keenish, mind you, so we took our unit and left theirs to Jack and Whatserface. Well, um, the long and the short of it is I let her drink too much and she passed out before we’d, um, you know.”

“Very clear,” she said drily.

“Yeah. So I just kipped on the other bed—it’s got two. She was still snoring when I woke up, so, um, I got out of it.”

“Was this in order to avoid the embarrassment?”

“Well, to save her from it, really,” replied George honestly, “’cos how many ladies wanna wake up and realise they passed out in a bloke’s room?”

“I get it!” she said with a sudden laugh, holding out a thin, tanned hand. “Lisbet Hall.”

“I’m George MacMurray,” said George numbly, shaking it. He seemed to’ve said something right, but he was blowed if he knew what. “Glad to meet you, Lisbet.”

“Likewise. Which motel are you at?”

“Marine Breezes.”

“Oh, yeah, I know it. Pale grey with a blue trim, a block back, that it?”

“Yes. The people that run it are very nice, actually.”

“Mm,” agreed Lisbet Hall with a little smile.

George eyed it suspiciously. “Is it that funny?”

“No, it’s just the wonderful light this has thrown on the middle-class suburban norms of the wide brown land, George!” she said with a laugh.

George MacMurray was flabbergasted, yes, flabbergasted. He just sat there with his gob agape.

“Sorry, did that shock you?” she said very, very drily.

“Shock me? It just about shortened me life by ten years, Lisbet! Suburban norms is right! If ya must know, I just about killed meself last night doing me best to conform to the flaming norms, but I can’t do it! How do people manage it? I asked Jack once and he just said—he’s a bright joker, mind, no chance he wouldn’t get what I was on about—he just said he closes his mind and goes with the flow, but it’s beyond me! I can’t make inane conversation about nothing, and I can’t work up any interest when they bore on about the wonderful cruise they went on and what the ruddy food was like—Fiji, it was, and neither of these flaming females uttered a syllable about the country itself, not even to say whether it was pretty, or hot! And when they tell ya what the colour scheme they’re planning for their bloody lounge-room is I can’t dredge up a single, solitary syllable in reply! Added to which, it was some bloody so-called Spanish place, charged an arm and a leg for ruining good lamb!”

“Aw, yeah. That place down near Byron? Yeah, I’ve seen it. Real Spanish food can be very good, but it takes a bit of getting used to. And that place looks to me like it’d be serving up the cuisine version.”

“Um, yeah. Well, spewy sweetbreads in white sauce and chopped-up kidneys were in there, and the lamb was beautifully tender but it had this sweet chestnut muck in it, and it was burnt on the outside—what the waitress reckoned was honey glaze.” He shrugged.

“Sounds about right, yeah,” she allowed. “Had spit-roast lamb in Spain once, just done with a bit of garlic and served with hunks of bread and some olives if you fancied them. Unbelievably good. But that was peasant food.”

“Right,” said George dazedly. “Sounds good. I don’t mind a bit of garlic with lamb. Can’t stand olives, though, I godda admit. Jack really likes them, always has olives and anchovies on his pizza.”

“That sounds okay. I haven’t had pizza for years,” said Lisbet Hall dreamily, hugging her skinny knees and gazing dreamily at the sea.

Uh—heck, she wasn’t a dole bludger, was she? She certainly didn’t look it, they were usually hairy yobs covered in tatts with extremely—extremely—stupid faces.

“To each his own, I suppose,” he said limply. “I usually have Hawaiian, or a meaty one—though that’s too much cholesterol, really. Um, ya don’t really like pizza, then, Lisbet?”

“Nope, not that: decided I couldn’t afford it. Used to work down in the Big Smoke—legal research in the Attorney General’s office—but they made me redundant at the age of forty-five and funnily enough all the downtown law firms only want to hire bunnies in zoot-suits to do their research. So I thought, if I hadda go on the flaming dole, why not come up here and get in a bit of surfing and swimming while I do it?”

“Right,” he agreed.

“I do a bit of harvesting, and I did get part-time work one summer, actually. Cleaning—Ocean View, it’s more up-market than Marine Breezes, it’s on the waterfront. Uh—over there,” she said waving a hand vaguely to their right. “Pinkish. The owners claim it’s washed terracotta, but pinkish is what it is. Only the woman that had left because she had this idea the bloke that had asked her to come up to the Sunshine Coast was gonna support her instead of vice versa came back, so I said they’d better let her have it, she needed it more than me, she’s got a three-year-old. Most of the other jobs around here are slinging hash at places like McDonald’s or waitressing, and they can hire kids to do that at less than they’d have to pay an adult. I’m not starving,” she said with a sidelong smile, “but pizza’s out.”

“Mm. Uh—no golden handshake?”

“On a researcher’s pittance? No way!”

Ouch. He looked at her sympathetically and said: “Well, at least you’ve got the sea and the sun.”

“Yeah: I’m rich!” said Lisbet Hall with a laugh.

“You sure are!” agreed George with feeling.

“Uh—look out here, they come,” she muttered.

A family group had appeared on the beach. Mum and Dad, two kids. George watched numbly as the parents set up their sun umbrella, sat under it and turned their ghetto-blaster on, and the kids, who were about eleven and twelve, ran down to the waves shrieking and shoving each other.

“Word for word,” he croaked.

“Eh? Oh! Yeah, more suburban norms. You gonna put up with it or head back to the passed-out lady at the motel, or what?” she said, getting up.

“Um—actually I feel quite hungry,” he discovered in astonishment. “Musta been that extra kip in the fresh air. No, no, well, mainly drank beer last night. Um, well, think she’ll still be asleep, the amount of the hard stuff she put away—we were out of miniatures by the time she asked for that last Coke. Well, or what, I suppose. There wouldn’t be a nice place that does toast and scrambled eggs, would there?” he asked wistfully, standing up and dusting the sand off his tracksuit.

“Nope. McDonald’s or nothing. What gave you that idea?” said Lisbet with a laugh.

“Uh—the Alice, I think. It was an awful holiday: Gwyneth, that’s my ex, was on me back the whole time: couldn’t do a thing right; but it was a really nice breakfast place. Tourist prices, of course, but they had the right idea about what a breakfast oughta be.”

“Cholesterol and white bread, right. Well, I can’t live up to that standard, but you’re welcome to come home and have some with me.”

George brightened. “Really? That’d be great!”

Lisbet Hall eyed him drily, silently promising herself that if the man walked into her main room and said “What a lot of books you’ve got,” she’d give him breakfast and sling him out, pronto. “Come on, it’s this way; you up for a walk?”

“Sure,” agreed George amiably, picking up his rubber thongs and trudging along at her side.

They went right along the beach towards the point, and he was beginning to wonder if her plan was that she’d paddle the board and he’d swim the rest of the way; but no, there was a steep track. They went right up it, to where it adjoined a proper tourist-type track that went as far as a sort of look-out, well, wider gravelled bit on the point itself, and then stopped. Then she led the way down the far side of the hill, over a lot of rough grass with a few little salt-tolerant plants and then through a belt of very bent, scraggy bush: must get the wind off the sea like nobody’s biz, and there they were, on the shore of a tiny, barren bay— Cripes!

“Shack, sweet shack,” said Lisbet, grinning widely.

“Yeah,” he croaked. Well, it was a good deal larger than a shack, verging on yer bungalow size, but it was constructed entirely of bits and pieces. Talk about recycling!

“Most of it belonged to my grandfather, he used it as a weekender, then when Uncle Bruce went barmy he came up here and enlarged it a bit and did his driftwood sculptures. He’s now running a successful gallery down in Byron, so the family have admitted that either he wasn’t as barmy as they thought or he’s got over it, take your pick. He owns the whole bay, he took one look at Byron and decided he’d rather die than retire there, so he bought up as much as they’d sell. It’s not subdivided, you see, so it was all or nothing. I’m just the tenant. He does accept rent, I’m not a parasite, and anyway, it’s not my money, it’s Centrelink’s.” She sniffed. “Hot-minted from their own pockets.”

“Yeah, Dad’s neighbour at Potters Inlet’s had a bit of that,” agreed George, as they went up onto the sagging verandah and she unlocked the front door. At least, it was serving as a front door, but he wasn’t too sure it had started life off that way. It was a flaking cream, with a large panel at the top that had obviously been designed for a pane of glass—George had a strong vision of it filled in with bubble glass, though he couldn’t for the life of him think where he’d seen a door like that. It wasn’t filled in with glass now, it was filled in with a serviceable piece of quite new-looking colour-steel. Red, like the Jardine place’s roof. Cheery.

“Um, that wasn’t once a bathroom door, was it?” he ventured.

“Dunno. Been here long as I can remember. That top panel’s new,” replied Lisbet cheerfully. “Well, this is it, make yourself at home.”

The front door opened directly into a fair-sized main room. George didn’t know what he’d expected, but it wasn’t this. It wasn’t done up trendily—no. Nothing in sight looked like it had been stripped and revarnished, and, contrariwise, nothing looked like it was supposed to be “distressed”. It was just genuine old stuff. Not junk, stuff. The floor was covered with half a dozen different old lino patterns—oops, no, the bit they were standing on, about two metres square, no, under two metres, the bloke musta been really glad to sell that to her, was very new vinyl. Yellowish-brown Spanish tiles, the sort of pattern that had been popular some time before the smooth, joinless sandstone look came in, and well before the genuine natural woodgrain fake floating-floor look that was currently favoured by cretins that wanted their kitchen floor to look like a wooden floating floor laid down over whatever had been there in the first place. Here and there on top of the linos were carpet offcuts—gee, that over there was a bit of floral Axminster, sliced right through the bunch of roses. No-one had made any attempt to re-cover the furniture, so the couch, which was about as old as that dead-elephant one in the Jardine place, was just saggy greyish-fawn plush, with a nice granny-square afghan over its middle section, and the two armchairs were respectively a huge old wooden-framed thing, kind of like a planter’s chair only not enough to be sold as one for megabucks, with a fawnish plush upholstered seat and back that wasn’t quite the same shade as the couch, and a horribly buttoned chunky thing in grubby pink brocade. Nothing had been done to disguise this abortion: it just sat there in all its pinkness.

“Don’t sit on the pink chair, it’s hard as buggery,” said Lisbet in a detached voice.

“Right, I won’t,” croaked George. “Where the Hell did it come from?”

“From a suite that belonged to my grandmother. Um, early Sixties, I think it dates from.”

“Sixties?” croaked George.

“You’re thinking in clichés. She was the sort that always went to the nice shops and woulda voted not to let the Beatles in the country if they’d given her a vote. They had the suite for years, never had a mark on it. Us kids weren’t allowed to go into the front room except on very special occasions. Then she decided to redecorate and ordered Grandpa to get rid of the lot. So Uncle Bruce grabbed one of the chairs for up here and Aunty Darryl grabbed one for the weekender she was living in, having been even barmier than him for years—they hadda be, self defence against Nanna, get it?—and the sofa went to auction.”

“Why didn’t your uncle grab it as well?”

“Hard as buggery to sit on,” replied Lisbet calmly.

“Sorry I asked!” admitted George with a laugh. “Does the fireplace work?”

“Not too good, no.”

“Okay, next question, is that a dead bear in front of it?”

“No, it’s a recycled fake-fur coat a friend’s neighbour had put out for the hard rubbish.”

Good, so she did have some friends! “It looks really like a bearskin,” George admitted, grinning.

“Yeah: I took the collar off, it was terribly frowsty,” said Lisbet, making a face.

Alas, at this point George MacMurray collapsed in horrible sniggers.

“Yeah,” agreed Lisbet, grinning. “I’ll just be in the kitchen. Um, the divan under the front window is miles more comfortable than the sofa or the chairs, actually, if you wanna sit down.”

“Right, thanks. I’ll just look at your books...” said George in a vague voice, wandering over to the bookshelves that lined the far wall, the fireplace wall to the left, and most of the right-hand wall under its mismatched windows.

Smiling a little, Lisbet went out through the door in the far left-hand corner of the room.

When she came back he was sitting on the divan under the front window, which was built out in what might have been based on the idea of a bay but hadn’t got that far. Lisbet thought of it as a hutch: its floor, at windowsill height, was really useful for putting large pot plants and mugs of coffee on. He was reading an orange-trimmed paperback book.

“Hey!” he said eagerly, looking up with a grin, “you’ve got some really old P.G. Wodehouses!”

“Yes. Most of them came to Uncle Bruce from one of his uncles, but he didn’t want them.”

“Dad’s got the Jeeves volumes and quite a few of the older ones, but not this one. I like the really old ones; it’s interesting, isn’t it, to see him developing his style?”

“Yes. I enjoy them for themselves, too, it always surprises me how modern they seem, actually.”

“You’re right,” he said thoughtfully. “Not as mannered as the Jeeves ones, I suppose.”

“Mm.” She put the tray of coffee and toast down on the coffee table. George had had experience of coffee tables people shoved in their weekenders. The unbearable types, the sort that blahed on unendingly about “just a weekender”, only when you got there it was restored and tartified to Kingdom Come, favoured yer genuine sea chest or old travelling trunk, strapped and brass-locked and covered in how’s-yer-fathers—huge old nails or, take your pick, genuine faded old steamship labels. Honey had a very interesting story about a mate of Barry and Kyle’s, also in the antiques trade, with his Internet searches—old labels were very collectible—his colour printer and his dried-in-a-very-slow-oven after being left soaking for three days in a very weak solution of tea. Yeah. That or the up-themselves types bought a driftwood one from some place like Lisbet’s Uncle Bruce’s gallery. More decent types—good old Mac Simpson from the uni came to mind—just slung something that the family had worn out in there. Mac and Helen’s was a genuine Seventies brass frame with the coating coming off in uneven patches, and the heavy glass top missing because for their Jim in the good old bye and bye had dropped a large piece of his motorbike engine that he shouldn’t have had in the house at all on it and through it, proving empirically that those heavy glass Seventies coffee table tops weren’t as hardened as what you’d imagined they were. Like that. Naturally they hadn’t replaced the glass, they’d simply shoved a bit of trimmed plasterboard in there, Mac as a great concession slapping a bit of paint on ’er, left over from when they did up the loft over the garage, allee same like the plasterboard, the year his sister’s boy came to board with them while he was doing his degree.

Lisbet’s coffee table was different. It wasn’t made of old wooden crates—those were getting like hen’s teeth in the 21st century, actually, and she’d sensibly used hers as bookcases for some of her taller books, and in fact in the case of two had put one on top of another—nailed, he’d had a quick look while she was getting the breakfast—and put books inside them and a big pot plant on top. Nor was it a trendy recycled door—George had seen a few of those in his time, too. On the other hand it wasn’t plastic beer crates, either, and this would be, at a guess, because whole crates of beer cost money that she didn’t have, plus and required a motorised vehicle in which to be driven home, which unless the vehicleless front of her place was lying, she didn’t have, either—there was certainly no garage. Nope, Lisbet’s coffee table was a sheet of grey melamine on composition board, possibly technically the end of a desk, it certainly wasn’t long enough to have been a desk top, sitting on a support composed of what was technically builder’s rubble. Broken bricks, odd bit of concrete—like that. George recognised it at once, he’d seen a bit of it, but not cemented together and sitting in a lounge-room of any kind, not even in a weekender.

“Hey, this tabletop,” he said thoughtfully, “did it come from a hard rubbish collection?”

“Yeah. Dunno what it is, there was just it.”

Right.

Lisbet waited but he didn’t remark on the impossibility of moving a coffee table base made of builder’s rubble, even though it wasn’t actually a solid block, it was hollow, so she said affably: “I’ll never be able to move the bloody thing, of course,” and watched with a smile as he collapsed in awful splutters, nodding madly.

After that she wasn’t surprised at all when on being offered his choice of the mugs, he didn’t meekly take the awful Garfield one that was nearer to him, he said firmly: “I really hate Garfield, so if it’s all the same to you I’ll have the pottery one.”

“Fake pottery: mass produced,” said Lisbet mildly, turning the tray so as the mug was in front of him.

“Aw, yeah: smooth. Mum gave us a set one Christmas, woulda been the year our Tracy turned three, I think, but bloody Gwyneth wouldn’t use them because they weren’t hand-thrown artefacts leaching lead like billyo from their badly fired, lumpy glazes. Should of seen the writing on the wall back then, really.”

“Yeah. Have some toast before it goes cold, “said Lisbet soothingly.

“Sorry.” George took some toast and since it was there, some jam. Maybe it’d help to get it down, ’cos it looked suspiciously like wholegrain stuff...

“Jefuff!” he said, swallowing. “This is fabulous bread, Lisbet!”

“Thanks. I sometime go mad and make it myself. It’s a mixture of wholemeal and white flour with a little bit of rye. No whole grains, I’ve got more respect for my teeth.”

“Me, too!” agreed George gratefully. It was the best bread he had ever tasted—no, the best brown bread, the best white bread was David Walsingham’s flat bread that he did in the wood oven. After a bit he found he was telling her all about it, and the oven, and the lamb David sometimes did in it. Ending: “Him and Bob Springer, the owner, they’re both very generous types, they refuse to hear of us paying in the restaurant, but it is their livelihood, so me and Dad don’t go over except for special occasions.”

“I see. So you won’t have tasted all his special dishes, then?”

“Nah, only half a dozen, and he knows neither of us likes anything too fancy, so if it’s—uh, well, forget them all, but for instance that pomegranate whatsit with duck, he wouldn’t ask us that night.”

“Right. Where do the pomegranates come into it?”

“Not sure, ’cos I’ve never had it, Lisbet! Well, Dot, his wife, she reckons that the, um, wouldja call them seeds? The little globules, they kind of sit on it, but there’s pomegranate juice in the sauce. Or did she say syrup? Um, forget. Red, anyway,” he finished feebly.

“Gee, pomegranates with duck... Well, it’s a nice dream, but I could never afford duck!” she admitted with a laugh.

“No, ’tis pricy. Their neighbour, Ann, she’s married to the guy who runs the crafts centre, she wants to raise them. Didn’t have much luck with her chooks—turned out to be capons—but she’s gonna give it a go. But see, the thing is, Bob charges so much in the restaurant that they can afford to put on duck whenever it takes David’s fancy. It’s the well-off baby-boomers that go for it, mostly,” he explained.

Lisbet shuddered. “What a waste of good food!”

“Yeah. There’s two sorts, the foodies that come up for it specially and ask for balsamic vinegar on their salad—drives ’im ropeable—and the ones that haven’t got a clue what they’re eating. But they’re all pretty awful, and apart from the gourmet thing, cut from the same cloth.”

“Right, the shiny four-wheel-drive set, eh?”

George rubbed his chin looking sheepish. “Yeah—no, drive a four-wheel-drive meself, but you’re not wrong. Mind you, Potters Road’s no picnic, and it’s useful if you wanna go on site, takes it without a blink, and then I did have to get out and look at a few piles of sandstone out in Outer Woop-Woop when I was on the hunt for recyclable stuff, came in handy then.”

“Yeah?” Lisbet spread jam lavishly on her toast. “So what do you do, George?”

George told her a lot about the job at Blue Gums Ecolodge, the design for the ecolodge, YDI and its workings, what materials he’d scrounged and where...

He came to after the second round of toast and the third round of coffee.

“Um, shit, sorry, Lisbet, blahing on!”

“Don’t be a nit, it was interesting.”

Had it been? George smiled weakly and asked her what sort of jam it was, he’d never tasted anything quite like it.

Okay, it was lilly pilly and a bit of plum, there was a big old plum tree behind the house that sometimes bore quite well.

“I haven’t done anything to the front, there’s not enough shelter and it’s too salty, but I’ve managed to get a sort of a veggie garden going out the back, if you’re interested.”

George was no gardener but he said quite truthfully he’d like to see it, so she led him through the kitchen. It was very old-fashioned, but clean. “Oh, you have got a freezer,” he said feebly.

“Yes; I’m not actually a Luddite,” replied Lisbet calmly. “This was the original kitchen, of course, the place was only one room and the lean-to,” she explained, opening the back door, “but Uncle Bruce enclosed the porch and built on the bathroom and bedroom.”

Right. Out of bits and pieces, but it looked quite sturdy. It wasn’t quite a wing, it had the same orientation as the older part of the house, but set back a lot further, its front wall about parallel with the back wall of the main room. The back door proper led off the little porch, interestingly papered in real newspapers.

“Uncle Bruce had a semi-trendy fit at one point back in the Seventies. The idea was he was gonna stick up anything that commemorated anything memorable.”

Uh—yeah. Well, it did have John Kerr’s dismissal of Gough Whitlam, yeah. And a bit on Watergate. Apart from that it seemed to be mostly lawnmower ads.

“Motor mower ads?” he said cautiously.

“And Vegemite ads.”

“Uh—right. Well, it is a cultural icon. Was this in his barmy phrase?”

“Yeah—well, barmier, but yeah.”

Right, goddit. They went past a sagging clothesline, cripes, with a real old clothes prop, he could just—only just—remember Gran having one of those, and through a thriving hedge—oh, lilly pilly, right—and here was the veggie garden. Entirely surrounded by—um, no, one far corner of the hedge was mixed hibiscus and bottlebrushes.

“The climate’s humid, so as well as the salt and the wind there’s powdery mildew to contend with: I’ve given up entirely on trying for zucchinis or marrows, and the only pumpkin that’s ever grown is a wild one, out beyond the hedge. Started off in a rubbish heap and just rampaged off. Beans usually do okay,” she said temperately. “And corn, but you have to watch out for the shield beetles.”

“Um, yeah. What’s that stuff?” said George weakly. There was masses of it—masses!

“That? Amaranth. Dunno why it does so well, but anyway, I’m not turning up my nose at it, my silverbeet and spinach croaked. You will see it as a bedding plant, true, but actually in Central America it was a favourite source of grain as well as greens before the Spanish started forcing them to grow corn in commercial quantities.”

“That right? I have seen it in, um, public gardens,” said George feebly.

“You would’ve, yes. –These are potatoes,” she added helpfully.

“I thought they were,” he conceded. There were masses of them, too. Giving in, he asked so what was in that other big bed, then?

“Broad beans. They seem to grow, so why not?”

“Um, yeah.”

“I’ve got some carrots in but I dunno if they’ll come to anything, haven’t had much luck with them, so far. My artichokes are coming on well, though: aren’t they beautiful?” she said, pointing at them.

They were, too: lovely big grey-green leaves, wonderful shapes... With a certain relief, George received the information that the tubs with the tripods in them all contained tomatoes, she’d found a variety that did well in tubs so she was sticking to it, and that those weren’t onions, they were garlic plants, but those over there were onions. Looked exactly the same to him. The huge old plum tree was just outside the hedge, at the back. They went down there and she explained that the other, much smaller trees, were pomegranates—no wonder she’d been so interested in David’s recipes—and olives, nothing much’d kill an olive.

“Yeah, um, what about other fruit?”

“I’ve got a mango coming along well in a tub up by the house, but I’ve failed dismally with apples, think it’s the humidity and the warm winters. But there’s a tamarillo in with the veggies, didn’t you notice it? –There,” she said, pointing.

It was next to the artichokes, so he’d just taken it for one of them that had bolted. Oops.

“Not a gardener, George?” she said, laughing.

“No,” he admitted.

“Well,” said Lisbet with a smile, “it may be odd, but it's all I’ve been able to get to grow, so far.”

“Uh—you’d be practically in the banana-growing belt up here, wouldn’t you?”

“Yeah, but I think it’s too salty for them just here.”

Okay, right. He couldn’t think of anything else his gran used to grow except cabbages. Oh—lettuces.

“Um, what about lettuces, or herbs?” he ventured as they returned to the house.

“See that there?” said Lisbet, pointing to the side of the new section of the house.

“Oh, yes! They’re doing well!” he congratulated her.

Lisbet sighed. “Japanese salad thing, some sort of Cruciferae. I planted them as an experiment and discovered they’ll grow like billyo but they taste revolting. And parsley, that’ll bolt to seed same as it did last year. I spent two years planting lettuces and losing the battle with the snails and caterpillars and the bolting and then gave up. But the herbs have done well, that’s sage all against the wall of the lean-to, and the big tubs are for basil and oregano. That dead thing was rosemary: it got an infestation that I could only describe to the nurseryman I bought the thing off as nits. Funnily enough he didn’t offer me a free replacement on the strength of it.”

“Cripes, really? I sometimes watch the gardening shows on TV—uncomprehendingly, usually—and I think rosemary’s one of the ones they sort of treat as, um, infallible.”

“They’re wrong, then. And before you utter the word ‘marigolds’, they came down with it too, in fact they were next to it and probably gave it to it, so please do not use the expression ‘companion planting’!”

“Wouldn’t dare!” said George with a laugh. “—Lemme get the door for ya.—I don’t even know what it is.”

“Lucky you. Why doesn’t someone stop these fucking self-appointed gurus?” said Lisbet moodily, going inside. “I’ve spent a small fortune on gardening books, and they’re all useless!”

“What I think,” said George slowly, following her in, “—mind, I’m only judging by the TV ones, here—is that everyone’s too shit-scared to stop them, because they’ve brainwashed the public into believing that when something goes wrong, it’s their—”

“—their fault!” she cried. “Yes!”

Their eyes met and they both broke down in hysterics.

After that it seemed perfectly natural to do the dishes together and then go for a stroll along Lisbet’s beach—it was noticeably windier than Ginger Bay, must be the angle it was set at—and pick up a few shells and bits of driftwood and gradually collect a bucketful of seaweed—there wasn’t much washed up, today—that the gurus reckoned was good for gardens.

“Hey,” said George thoughtfully as they reached the far end of the beach, “if your soil’s too salty anyway, won’t this stuff make it even saltier? I mean, besides the iodine and whatever else is in it.”

Lisbet’s mouth opened silently, but no sound came out of it. Then she took a deep breath and determinedly up-ended the bucket.

“Um, that’s just simple logic; I could be—”

“You’re not wrong!” she said fiercely, grabbing his arm and hugging it fiercely into her side. “Jesus, I’ve spent four years gathering the muck!”

“It is organic, I suppose it adds something to your soil.”

“Besides the salt! Yeah! Come on, let’s head back. Feel like a barbie on the beach?”

He certainly did, but he thought he’d better ring Jack, just in case he was panicking. Lisbet pointing out amiably that he could do both, they strolled back, arm-in-arm, and he used her phone—thank God she had one, she was bloody isolated out here.

Funnily enough the dames had both pushed off to their room and Jack was back in theirs.

“Joanne passed out, eh?” he noted.

“Yeah,” agreed George noncommittally. –The phone was in the kitchen and Lisbet was getting stuff out of the fridge.

“Junie reckons it’s not the first time.”

“Thanks for that, Jackson.”

“Yeah. Well, where the fuck are ya, George?”

“Oh—sorry, I’m at Lisbet’s place. Met her down the beach. She lives just over the point—north, but not too close to Queensland!” said George with a laugh. “Either literally or metaphorically, actually!”

“That’s good. Well, you planning on coming back some time in the near future or shall I grab meself some fish and chips?”

“Aren't you gonna spend the day with Junie, then?”

“Nope.”

“Uh, didn’t it go okay?” said George cautiously.

“It went okay, if ya like the sort with a brain like a hen. Make that a demented hen.”

“Jack, it was blindingly obvious yesterday that the woman had a brain like a demented hen, why did you encourage her if— No, all right, self-evident,” he sighed.

“So are ya coming back?”

“No, Lisbet’s asked me to lunch.”

“Is he on his own? Ask him over, George,” prompted Lisbet at this point, smiling a little.

George wasn’t too sure he wanted to share her with Jack; for one thing, females always fell for the joker! But heck, they’d come together, couldn’t leave the bloke on his ownsome. “Thanks, Lisbet. –You get that? Come on over here. –No!” he said loudly, turning purple.

Lisbet looked at him with a smile but got on with sorting out plates and cutlery for the barbie.

“Yes, she’s asked ya! Um, it’s the next bay up the coast, just, um—shit, can ya get here by the road, Lisbet?”

“Sort of, only it’s longer.”

“Right. Jack, go down the beach, walk north, that’s to your left—all right, ya know—go as far as the point and you’ll see a little track, hard left. That’ll take you up to the top of the point, it meets a proper tourist trail. Doesn’t lead anywhere, just up the top. Go down the far side, make your way through the bush, still heading northish, only about ten minutes, and then you come out at Lisbet’s bay. –No; ya can’t miss it, mate. Anyway, we’ll be on the beach with the barbie. See ya!”

“You could have mentioned there’s only the one house here,” said Lisbet drily.

“Uh-uh. Want ’im to have the pleasure of finding it out for himself.”

Of course he did! Smiling, she said: “Can ya grab that stuff, and then we’ll be right.”

“Sure. Uh—the barbecue?” ventured George as she headed for the door.

“The grill’s outside.”

Uh—was it? He followed her obediently.

Ooh, yeah, so it was! An old oven rack, by the looks of it, propped up by the side of the front steps. Lisbet, who wasn’t carrying anything, scooped it up, together with a great pile of driftwood that he’d assumed was Uncle Bruce’s leftovers, and they set off for the beach and the first real barbie George MacMurray had had since, to be strictly accurate, his engagement to bloody Gwyneth. He had cooked fish over a fire with Dad since then, but— Oh, boy!

… “Boy, this is living!” concluded Jack with a sigh, lying back full of sausages, the beer that he’d thoughtfully brought over with him, and Lisbet’s miraculous bread and lilly pilly and plum jam, quite some time later.

“Yep!” agreed George. “No argument there!”

Of course on the way home to Potters Inlet the bugger wanted to know why in Hell he’d spent the whole weekend in her pocket without doing the woman but George just shouted: “Shut up! She isn’t that sort! It wasn’t like that! She isn’t that sort, are you blind?” and: “Shut UP, Jack!” until he got the point and shut up.

Next chapter:

https://theroadtobluegums.blogspot.com/2022/11/backsliiding.html

No comments:

Post a Comment